-

Retiring My WASD V2 Keyboard

Eons ago (~2013), my spouse suggested a mechanical keyboard as a gift idea for me. It was a good idea! By then I had pivoted from freelance miscellany to a steady programming job, and having nice tools for the trade seemed appropriate. I got a switch tester, I researched, and ended up selecting a WASD (spouse’s initial recommendation) V2 87-key / “tenkeyless” keyboard with Cherry MX Blue switches and a set of custom, etched-label keycaps in a custom blue/grey/orange color scheme.

My 87 key WASD V2 on my perpetually messy desk back in 2013—taken on an iPhone 5s! The legends are laser etched into the keys, splitting the difference between starkly beautiful blank caps and usability by a typist who occasionally must hunt and peck. I still think the color scheme looks pretty good! At the time, the “buckling spring” IBM Model M was the consensus king of durable, classic keyboards with a great typing feel. Two intertwined aspects of that switch mechanism were said to be particularly important. First, that the switches had great tactile feedback when the spring “buckled” and snapped to trigger the contact; and second, that this tactile feedback was coincident with the switch activating (sending the “key got pressed” electrical signal). It was said that this allowed a frequent user to learn precisely how hard to press in order to activate the key without “bottoming out” and smashing the key to the low point of its available travel. The idea was that avoiding this shock would provide a gentler experience for your hands and fingers, and maybe even help to avoid repetitive stress injuries from typing.

I had had some wrist issues from computer programming by that point, so for my keyboard I picked the Cherry MX Blue switches because they, too, had strong feedback that was at least close to (if not precisely coincident with) the activation of the switch. Finely-made, durable, German, Cherry switches; n-key rollover (many keys can be “down” at once”); a solid, flex-free build; support for alternative layouts (e.g. Dvorak); the ability to replace key caps sometime in the future; just the right amount of stylistic flair: these were the reasons to get a mechanical keyboard at the time. I’ve never dipped my toe into alternative keyboard layouts, but otherwise those were my personal reasons for feeling ready to get a mechanical keyboard.

Typing Comfort

It remained a familiar and comfortable typing experience through the decade that I used it. In the beginning, I was coming from typing on laptops or other low-profile keyboards, and I remember it taking a little time to adjust to the relatively deep 4mm travel of the switches and the various angles of the (Cherry? OEM?) profile keys. But it did come to feel pretty comfortable. I’ve had fewer bouts of wrist issues, but I’m not sure how much credit the keyboard deserves for that. For me, I think the more important changes were working at a desk at a good height, not working on a laptop on a couch, and switching to a vertical mouse. As predicted by internet skeptics, I never got so precise with my typing as to be able to consistently avoid bottoming out the blue switches. But I do like the click and switch activation being in the middle of the switch’s travel. I can go several keystrokes at a time without hitting the key all the way down, and the rest of the time I think the feedback helps my fingers to have at least slowed down by that point.

WASD Etched Keycaps

The keycaps turned out not to be very high quality. The etched legends felt rough, especially at first. I thought that some kind of finishing could have helped with this, but tellingly I haven’t noticed similar etched keycaps from any other vendors, so it may just be impossible to do nicely. I also spent the first few years with my desk in a challenging environment, where the keyboard was in almost daily, direct California sunlight. This, I believe, seriously discolored the keycaps (most noticeably the blue and grey ones). They looked disgusting and I worried that I must have especially filthy hand sweat or something. No amount of dish detergent or other soaps would remove the “stain”, though, and I eventually figured out that this yellowing is the behavior of additives and coatings meant to protect plastic from UV light.

The best photo I could get of the probably-sunlight-caused discoloration of the original keycaps (and a bit of a look at the rough etched letters). These tumbled around in a junk box for a few years so, yes, they are also dirty. It was fun to pick a color scheme, to make some minor edits to the legends, and to have a keyboard that looked unlabeled like a simplified 3D rendering. At the time it felt like such customization was a major reason why one would buy a roughly $200 keyboard instead of just using whatever was lying around. But once I bought new keycaps the overall experience of the keyboard was much nicer.

Domikey Keycaps

In the Fall of 2020, the covid pandemic was still raging, my kids were not returning to in-person school, I was in full Super Dad mode trying to work from home while also making donuts and teaching kids to ride bikes and wrangling everyone up to Erie to hangout (masked!) on the beach. Depending on how that particular day was going, I was either ready to give myself a healthy little reward or so far gone that I was obsessively trawling mechanical keyboard forums to keep myself from screaming. So I bought fancy keycaps! I bought Domikey brand, doubleshot ABS plastic, SA* profile keycaps in the Classic Dolch color way. I love the “big centered letter” style of legends, the black/grey/red Dolch scheme felt like a subdued echo of my original grey/blue/orange, and I was sufficiently convinced by accounts on geekhack and r/MechanicalKeyboards to try the comparatively tall, sculpted, “SA” profile (or at least Domikey’s approximation of the canonical SA profile keycaps available from Signature Plastics).

My WASD V2 with the Domikey doubleshot ABS, SA-clone, Dolch keycaps—its final appearance before retirement. Sorry I don’t have a better glamour shot! I love these keycaps. I think they look fantastic. After an adjustment period, the tall, spherical, not-technically-SA-profile keycap shapes felt more comfortable and easier for me to touch-type with than the original ones. The most unexpectedly welcome change, though, was their effect on the sound of the keyboard.

Click clack thock

In 2024, many conversations in the mechanical keyboard hobby read like an audiophile forum, with people creating and eliminating voids, applying greases, adding weights, adding or removing layers of foam to prevent or permit the transmission of vibrations, and selecting materials from polycarbonate to brass in the pursuit of ever more precisely defined acoustic profiles. That’s fine and good, but not particularly appealing to me. And yet! The deeper, mellower sound of my keyboard with the new keycaps was such an improvement over the thinly clicky sound of the original keycaps, that I, too, may end up stuffing a keyboard with bandaids and kinetic sand someday.

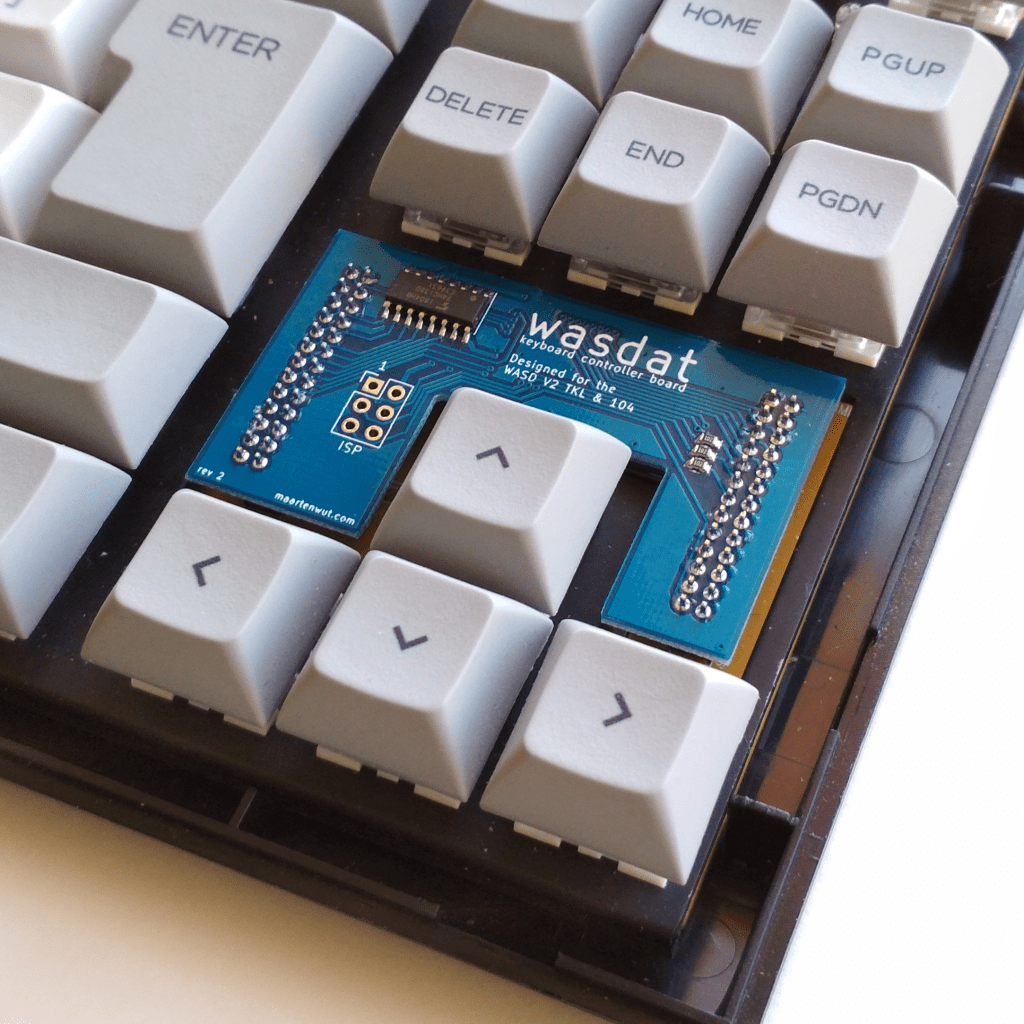

Wasdat Controller Board

As part of the same 2020 “let’s upgrade this keyboard” impulse, I also bought a “Wasdat” (GitHub) replacement controller for it. This made the keyboard compatible with the powerful yet friendly VIA keyboard configuration software. Other than a tweak or two to the media keys, I didn’t end up taking much advantage of the flexibility this offered over the original configuration-by-DIP-switches. I will say that it was extremely cool and futuristic to pull a little circuit board out of its special little nook in the keyboard and replace it with a new one, and that ten minutes of feeling like I was an engineer on Star Trek was worth the ~$25. I’m not sure why WASD had the original controller on a daughterboard like this to begin with, but being able to easily upgrade it added to the professional feel of the keyboard. It’s probably not widely used, but I was disappointed to see that the successor V3 keyboards just have a soldered-in-place controller.

A photo of the wasdat controller, taken from the anykeys website. Decline Phase

By 2024, I started having issues with missed and doubled keystrokes. Inevitably, it seemed to affect keys I use frequently—Tab, “e”, and “o” were all pretty inconvenient to be unreliable. I was also growing tired of its clickiness—even its more muted, nicer-keycaps clickiness—while on Zoom calls. I later desoldered a few of the problematic switches and opened them up, and it looked to me like they were suffering from a decade of dust and hairs and other debris. I bought some new Cherry MX Blues to replace the problem switches with, but my crude soldering seems to have caused a problem where every so often a handful of keys will stop working for a minute or two.

While I was in there, I did also try stuffing some sheets of foam into the case, and it sounded and felt a bit nicer! Honestly I’m still a little tempted to buy one of the fancy aluminum cases WASD now sells—the plastic case is held together primarily with tabs that snap into place, and of course I broke one when opening it up to do the controller swap a few years back. This keyboard is sentimental to me, and in some ways I really like the idea of having and using a durable tool that’s old enough to attend middle school.

But I’m also worried that the “dead keys” issue is because I damaged the circuit board soldering in new switches. I don’t think computer programming is about typing all day, but I do enough typing that I need my keyboard to be a tool that I can rely on. So in the end, I did buy something new, but that’s a subject for a different post.

-

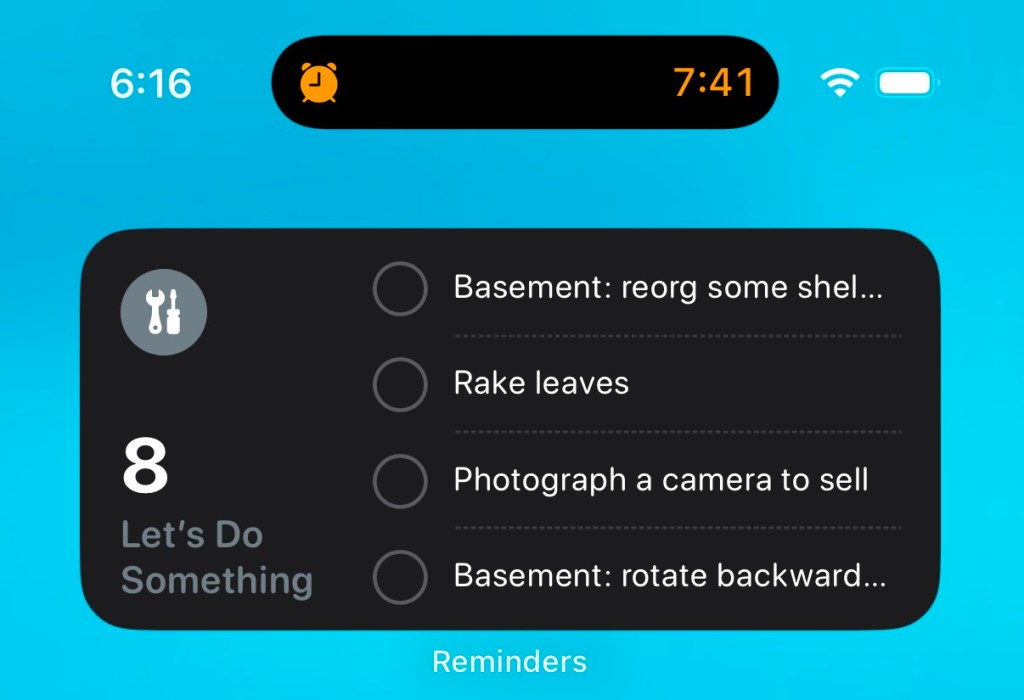

Shortcut for Randomizing Reminders List Order

Every so often I end up making a new list of low-priority things I have been meaning to do. I often do this in the Reminders app on iOS, and I always do it with a plan to regularly check that list and, as I imagine it, occasionally spot some little task that feels just right in the moment. Instead, I forget about those lists, I only rarely complete those to-dos, and then only when something else brings one of them to mind. As the calendar turns over, even I can’t resist a little bit of a hopeful attempt at a productivity hack, so I’m going to see if I can set myself up for more success in 2025.

My reminder widget, early in the morning before I’ve officially woken up. What I’m doing is putting a large widget on my phone’s home screen with the current iteration of this list. The point, for me, is that the full list includes a relatively large number of varied things to do, and that these tasks have no particular priority or order in which they should be done. I want to glance at this list one day and think, “yeah I can bundle up some clothes to donate”; on another day decide to put up some shelves; and on yet another feel up to preparing some cameras for eBay.

Later that day, it shows a (mostly) new set of tasks. But the widget only show four items, and neither the Reminders app nor its widget has a “shuffle” mode. I needed a way to randomize the order of this list so that I would be presented with a different set of four items every day or so. I created a simple Shortcut to do that. Here’s what it does:

- Shortcuts has a built in method to get items from a Reminders list. Even better, the Sort option for this lets you sort them in random order. So already we’ve got our randomized list of pending to-do items!

- The problem is preserving that random order: there doesn’t appear to be a way to have a Shortcut set the manual sort order of a list of reminders.

- My first attempt to solve this was to iterate through the randomized list, adding a new copy of each to-do item to the list and deleting the original—thus rebuilding the list from scratch each time. But frustratingly if understandably, it’s impossible to have a Shortcut delete Reminders items without prompting the user to approve the deletion each time. Completing each item instead of deleting it would mean amassing a huge pile of duplicate completed items in the list, which felt wrong.

- This means we have to find a way to save the randomized order by only editing the existing items. The Due Date field is a supported Sort field in the Reminders app, and it can also be set by a Shortcut. I’m not using Due Date for this list of low-priority / no-due-date tasks, so I’m free to use it as a blunt way to order reminders. So now I loop through the randomized list of reminders, and set the Due Date for each one to be:

[current date] + (120 + [“repeat index” of the randomized list]) days

This ends up setting one item to be due in 121 days, another in 122 days, etc, etc. I picked 120 days as an interval far enough out that I won’t usually be bothered by seeing these reminders in the Calendar app.

- That’s it for the script, so now we just need a way to run it regularly. I use a daily sleep schedule on my phone, so in the Automation tab of Shortcuts I already had a “When Waking Up” entry. I set this to run my Shortcut.

This means that the list gets reordered soon after I wake up, but the widget itself doesn’t update immediately. For me that’s OK; again, none of these tasks are time-sensitive and I just want to see a new set of them out of the corner of my eye every so often. A few days in, I can confirm that the technical side of the system works. I haven’t actually done anything from the list yet; if anything, so far this has only prompted me to add more reminders to it. Cynically, I think most productivity hacks only function to perpetuate themselves, so if that’s all this accomplishes I can’t say I’ll be surprised.

Screenshot of the Shortcut But hope springs eternal! If you’d like to try this, here’s a link to the Shortcut—you’ll need to set the Reminders list to your own list to use. I’ll try to revisit this is 6 months or so to report on how my completion count is looking.

-

Farewell, Penn Ave Satellite Dish

Taken in late 2023. Nikon FE2 Nikon Series E 50/1.8 Kodak Plus-X I never knew what this satellite dish at the corner of Penn Ave and Mathilda St was. The aggressively unlabeled building it was next to suggested something more prosaic than the TV or radio station that I liked to imagine was broadcasting, for some reason, from a ground-level parking lot.

Even in the generally dense east end, Pittsburgh has a real mixture of roughly 60+ year-old pedestrian-focused street-fronting density, and somewhat newer attempts to get with the later 20th century times by creating a more car-friendly landscape. Even now, when most of the architects, neighborhood groups, and city planners would rather skip devoting any more surface area to asphalt, we sometimes get stuck with the decidedly suburban-looking First National Bank branch newly built at the corner of Penn and Negley Avenues. So it was nice that this fairly ugly building with small windows and a large surface parking lot could at least offer a little visual interest in the form of a surprisingly large satellite dish. I’ll miss walking by it.

Taken in mid 2024. Agat 18K, Kodak Pro Image 100 -

Unboxing the World

I haven’t listened to many “general interest” podcasts (or radio shows, or YouTubers) in a while—you know, This American Life, Radio Lab, and their less-famous or non-NPR or more-niche-specific analogs. I’m a curious person, I like learning about things, and I will even admit to enjoying telling other people all about the things I know without them necessarily inviting such a lecture. So what happened?

First, another question: are “unboxing” videos still a a thing? Off the top of my head, I think of them as having started around the time of the early iPhones. They were videos of someone taking a new and generally high-end product out of its packaging. Usually there would be some light editorializing about materials, a dash of plastic film ASMR, and sometimes a brief look at the product itself. But the extent to which these videos did resemble a review was strictly for the purpose of communicating the relative pleasure of experiencing the object purely as a product and not as a tool. That format meant that the only qualification for creating these videos was simply having that hot product before most other people did, and the only thing these videos delivered was the thin, vicarious experience of opening the box.

To me, unboxing videos have always seemed insane. The host was invariably someone without much specific insight into the product category, with YouTube audience thirst oozing out of every pore, and sometimes an undercurrent of desperation spurred by the uncertainty of whether the views will pay enough to justify the expense of purchasing the product. I absolutely recognize the nerdy impulse to dive headfirst into as much content about your interests as possible, but unboxing videos always seemed like a pure “spoiler” to me: congratulations, now if you buy that product yourself, your own reactions will slip into a track already carved out by someone named Josh who is not a fellow obsessive but instead just someone with $1000 and an ambition to make a popular video.

So, yes, to tie this back together, there’s a kind of reporting/essaying common to those podcasts that feels too much like “unboxing the world” to me. Millions of young people will no longer get to have the experience of bumping into the term “desire lines” unprepared! Why? Because there are fleets of self-consciously thoughtful people, armed with microphones, plying the seas of emerging subcultures, niche industries, and overlooked places for anything that could feel like a discovery. Unlike when a friend tells you about something they have recently encountered, each overturned rock is offered with a kind of public act of introspection that seems to close the subject off to further contemplation even while it offers no conclusions. The personal, almost confessional tone of these podcasts becomes more quietly unsettling with each additional episode: learning about epigenetics just blew your mind last week, and now talking to someone from a failed 1960’s commune has you once again awestruck by the complex beauty of existence? Is this a meta-narrative about a personality disorder?

As I have gotten older, moments of genuine wonder—times when something new lets you glimpse a terrain of possibilities—have gotten more rare, and consequently more precious to me. As you age there is more that you (think you) already know, and you also must put in more work to maintain the curious and open mindset that enables these experiences. So I think the strength of my reaction is partly driven by disgust at the formulaic bulk commercialization—however well-intentioned and poorly-compensated—of this kind of feeling. But primarily I stopped listening because however many of those nuggets are still unknown to me, I would prefer to experience discovering them by myself or with friends.

-

Old Millenials, LLMs, and the Internet

I have been thinking a lot about the internet (the web?) lately, especially vis-a-vis LLMs, and I keep trying and failing to write down my thoughts. So rather than keep attempting to wring a coherent argument out of myself, I’m going to take the coward’s way out and write up some loosely-connected bullet points.

- I’m approximately 40, and nearly all of the decision makers driving the recent AI/LLM explosion are roughly my age or older. I think that if you experienced the late 90’s through iPhone explosion of the web—if you were old enough to experience a need and then (still) flexible enough and curious enough to dive into meeting it with new technology—then LLMs can feel like the apotheosis of the internet. If you are old enough, then you have sat with friends wondering what actor was in a film, or what the name of a musician’s side project was, or how to make guacamole, and been entirely unable to answer the question in that moment. And as time went on you would have experienced asking Lycos or Yahoo or AltaVista or Google about more and subtler things, and been delighted as more and more of them had useful results. I think the magic of living through that transformation established a kind of trust in the internet as a communal body of knowledge (even if most of those now-40-year-olds were also posting nonsense on Something Awful or 4chan).

- That content was coming from a wide variety of sources, too. There were central consolidators of information like Wikipedia and The IMDB, but it was also very common to find your answer on someone’s personal webpage on Geocities or Angelfire, or on a dedicated community / fansite, or a phpBB forum, or one of seemingly innumerable university professors’ websites. My recollection is that simply making a website—any website—was fun, and novel, and seemed like a way to build a presumed-to-be useful skill, so people would set out primarily to learn HTML and only secondarily (at least at first) to share their knowledge about fish keeping or making sourdough or the lyrics of The Doors. The hosting was free, the time was an investment, and beyond “maybe put AdWords on it” there wasn’t much of a business case to be made and thus little in the way of an invisible hand forcing consolidation in the market to provide information about the South Jersey ska-punk scene.

- Now much of that kind of personal content has moved within platforms. Some of those, like Reddit or Fandom, are within view of a Google search, but the most devoted “interest community” activity is now enclosed within Instagram, Facebook, Discord, Telegram, TikTok, etc, etc. Self-hosting an open community on the internet has a lot of challenges (technical, financial, moderation, etc) so this is pretty understandable, but it feels like a tragedy to me. To whit, film photography is seeing a resurgence, but if you Google for help with your parent’s old camera the best results will probably be on Flickr from more than a decade ago, because the relevant subreddits are more casual and there’s no easy way to find the right Discords and Facebook Groups when you are new to the hobby.

- Personally, I think Google would be better off today if they had invested in solving those problems to enable people to keep such conversations happening out in the open. And not only for LLM purposes; search results are terrible now partly because there is so much keyword spam content, but also because there’s scant new hobbyist content (leaving only the 2010 Flickr threads about that hand-me-down Nikon). There is, as people have found, Reddit, but attempts to game Google through spam on Reddit are already testing the dedication of volunteer moderators.

- I hope that LLM-mania will prompt the tech giants to encourage a return of the kind of self-consciously open knowledge sharing that flowered on the early web—and to be clear, I hope they can encourage that by creating financial support for that knowledge sharing in addition to relying on good UX and public spiritedness. But Google has YouTube, Meta has Facebook and Instagram and Threads, and for the moment OpenAI has ambiguous laws and an Uber-style habit of taking first and only asking for permission later if forced to. While it is true that advances in AI make it easier (or at least possible) to get value out of existing pools of data, I think there is something almost mercantilist in the way companies are focused solely on the value of their proprietary datasets. So I don’t think a Google or a Meta will feel that they have anything to gain from enabling the creation and sharing of data that is not exclusive to their own use.

- Reporter James Surowiecki’s The Wisdom of Crowds turned 20 years old this May. I’ve never read it! But I did it hear highly condensed accounts of it in both more and less formal presentations in the Bay Area in the years immediately following its 2004 release. Such crowds were at their wisest when averaging a number, as in guessing the weight of an ox at a county fair (the anecdote which invariably accompanied any mention of the book), or assessing the quality of a restaurant. So for a time people were very interested in things like tagging systems that might offer a way to make anything from LinkedIn resumes to Flickr photos roughly reducible to something that could be navigated and ranked with simple arithmetic.

- I’m no machine learning PhD, but as I understand it the current explosion of LLMs is enabled by a combination of techniques going back to the likes of Word2Vec that can represent text (among other things) as many-dimensional grids of numbers, and the increasing power of graphics cards to process more of those matrices in much less time. So now an LLM can summarize a page of text, and it is similarly a matter of math. But at a product level, I think people (likely my age!) are mistakenly imagining that recipes can be aggregated with the same kind of deterministic Excel math used to summarize movie review scores. One prank pizza recipe can cause subtler havoc than one prank product rating.

- For now, there are broadly two ways that an LLM can answer your question.

- One, is for the LLM to answer the question “itself”, drawing from its base dataset (which we can shorthand as “the entire web”) and modulated by whatever training or fine-tuning it received (shorthand as showing it example question/ answer pairs, or people giving proposed answers a thumbs up or thumbs down). This is fun and impressive, because it seems like the internet has become sentient, it feels like talking to an all-knowing demigod, and at its best these answers appear to distill the entirety of human knowledge about a subject into a concise response. On the other hand, because the answer is being sieved out of such an enormous soup of data, these responses sometimes exhibit inaccuracies that weren’t present in the source material.

- The other way (called Retrieval Augmented Generation, or RAG) is for a process to search a body of content for text likely to have the answer, and then have the LLM answer the question drawing only from the text of those sources. This tends to create responses that hew closer to the source text, but it’s a bit less magical because reading a Wikipedia page and summarizing the first paragraph is something most people could just do themselves, and seeing the sources cited reminds people of how much they may not trust Wikipedia, or a given newspaper, or Reddit, or a blogpost.

- Something that I imagine is tantalizing to founders about the Wisdom of Crowds framing is that each individual contribution is presumed to be almost worthless—so Yelp, for example, is providing more value by aggregating than you do by writing your individual review. I like the idea of a universe where there can be millions of individual pages and conversations about (say) film photography, but I think that (perhaps outdated!) view of the internet may play into the idea that none of those non-professional sources are particularly valuable individually, and that an LLM trained on them summarizing an answer out of so much photography text soup is what is really providing value. Meanwhile, if there really are only a handful of sources to draw from, it becomes clearer that they are the actual resource, that they are providing the value—and that they should probably be paid.

- I will say that I think both answering strategies are and will continue to be useful in practice, and that different people may want different kinds of answers to the same questions—I may want the zeitgeist-thru-LLM’s quick answer to what temperature to bake salmon at, but lots of context around what is the best laser printer; you may want the opposite. But if the authentic human conversations remain in closed communities (maybe even moreso in flight from AI), and the display-ad websites disappear along with their Google traffic, and if everywhere on the internet is flooded by okay-ish AI-generated empty content, then I don’t know where new source material is going to come from. It’s genuinely exciting that we’ve achieved the early 2000’s goal of creating the greatest interactive encyclopedia ever (boy did computer nerds love talking about the Primer in Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age). But the information ecosystem of the internet will have to evolve if that encyclopedia is going to continue to be updated into the 2030’s.

-

A GitHub Copilot AI Anecdote

I’ve been watching Three Body—the 2023 Chinese television adaptation of the same Liu Cixin science fiction novel that Netflix also put out a version of. My copy was found on the high seas shortly after the release of the series, but it’s now available on a few streaming services. I was about 20 minutes into watching Episode 13 when the subtitles suddenly lost their sync with the video; text appeared on screen about 15-20 seconds after it was spoken. I tried Plex’s feature for downloading alternate subtitles, but each one exhibited the same problem. I spent $2 to just buy that episode from Amazon, skipped ahead to where I had left off, and even that had the same misaligned subtitles. This post is the story of how, having failed to buy my way out of the problem, I used AI to fix it.

I have a subscription to GitHub Copilot through my work, so after a rough assessment of the problem I opened the offending srt caption file in Visual Studio Code and submitted this prompt in the chat window:

The srt file I have open is incorrect; all captions are set 15 seconds too late beginning with caption number 225. Please correct the srt file, altering the time codes for all caption entries beginning with 225, to have them appear on screen 15 seconds earlier.

What I wanted was for the robot to just echo out a repaired srt file, but instead it offered a Python script that could fix the problem. Apologies for the spoiler, but anyone skimming this post for a solution to their own caption file problems might want to skip a bit farther down:

To adjust the time codes in an SRT file, you can read the file line by line, identify the lines that contain time codes, and adjust the time codes as needed. Here’s a Python script that does that:

import re from datetime import timedelta # Open the SRT file with open('Three-Body.S01E13.CHINESE.WEBRip.x264-ION10[eztv.re].srt', 'r') as file: lines = file.readlines() # Regular expression to match time codes time_code_regex = re.compile(r'(\d{2}:\d{2}:\d{2},\d{3}) --> (\d{2}:\d{2}:\d{2},\d{3})') # Time delta to subtract time_delta = timedelta(seconds=15) # Adjust the time codes for i in range(len(lines)): # Check if the line is a time code line match = time_code_regex.match(lines[i]) if match: # Check if the caption number is 225 or higher caption_number = int(lines[i-1].strip()) if caption_number >= 225: # Parse the start and end times start_time = datetime.strptime(match.group(1), '%H:%M:%S,%f') end_time = datetime.strptime(match.group(2), '%H:%M:%S,%f') # Subtract the time delta start_time -= time_delta end_time -= time_delta # Format the new time code new_time_code = f'{start_time.strftime("%H:%M:%S,%f")[:-3]} --> {end_time.strftime("%H:%M:%S,%f")[:-3]}' # Replace the line with the new time code lines[i] = new_time_code # Write the adjusted lines back to the file with open('Three-Body.S01E13.CHINESE.WEBRip.x264-ION10[eztv.re].srt', 'w') as file: file.writelines(lines)This script opens the SRT file, reads all the lines into a list, and then iterates over the list. For each line, it checks if the line is a time code line and if the caption number is 225 or higher. If both conditions are met, it parses the start and end times, subtracts 15 seconds from each, and replaces the line with the new time code. Finally, it writes the adjusted lines back to the file.

Please replace

'Three-Body.S01E13.CHINESE.WEBRip.x264-ION10[eztv.re].srt'with the path to your SRT file if it’s different.The script looked decent enough at a glance, although it didn’t include any details about how to run the script. I knew to put it in a

.pyfile, and although I have very little experience with Python I could guess that the script might need to be run withpython3rather thanpythonon my Mac laptop (which turned out to be true, but perhaps due to some quirk of my own setup). The script also edits the file in-place, rather than saving the result out to a new file, which I would consider bad practice; arguably it should take the srt filename as an input parameter, but then again we’re just trying to solve a single, weird, one-off problem. So we’ll deduct a couple of “ease of use” and “best practice” points, but more importantly the script didn’t work!First, it failed to import the “datetime” module—the syntax highlighting in VS Code made that obvious enough, but the IDE’s proposed fix of

import datetimewasn’t correct, either. So I addedfrom datetime import datetimeto the top of the file and ran the script against my local copy of the srt. I didn’t bother to look very closely at the result—in my defense, it was 10:30pm and I was in “watching tv” mode, not “I am a software engineer” mode—and copied it to the Plex server. I restarted playing the episode where I left off and… now there weren’t any subtitles at all!Let’s look at a snippet of the edited srt file to see if we can spot the problem:

223 00:16:25,660 --> 00:16:30,940 Correcting them is what I should do. 224 00:16:31,300 --> 00:16:45,660 At that time, I thought my life was over, and I might even die in that room. 225 00:16:51,020 --> 00:16:54,500This is the person you want. I've handled all the formalities. 226 00:16:54,500 --> 00:16:56,420You know the nature of this, right?Subtitle formats are actually pretty easy to read in plaintext, which I appreciate. And a glance at the above snippet shows that GitHub Copilot’s script resulted in the timestamp of each entry running immediately into the first line of text of that caption. I’m trying to keep this relatively brief, so I’ll just note that a cursory search turned up a well-known quirk of Python’s

file.readlinesmethod (which reads a file while splitting it into individual lines of text), which is that it includes a “newline” character at the end of each line—and so the correspondingfile.writelinesmethod (which writes a list of lines out to a file) assumes that each line will end with that “now go to the next line” character if necessary. As someone who doesn’t often use Python, that’s an unexpected behavior, so to me this feels like a relatable and very human mistake to make. But anyone used to doing text file operations in Python might find it a strangely elementary thing to miss.After adding the

datetimeimport, fixing the missing linebreak, changing the script to save to a separate file with an “_edited” suffix, and adjusting the amount of time to shift the captions after some trial and error (not Copilot’s fault), we end up with this as the functioning script:import re from datetime import timedelta from datetime import datetime # Open the SRT file with open('Three-Body.S01E13.CHINESE.WEBRip.x264-ION10[eztv.re].srt', 'r') as file: lines = file.readlines() # Regular expression to match time codes time_code_regex = re.compile(r'(\d{2}:\d{2}:\d{2},\d{3}) --> (\d{2}:\d{2}:\d{2},\d{3})') # Time delta to subtract time_delta = timedelta(seconds=18) # Adjust the time codes for i in range(len(lines)): # Check if the line is a time code line match = time_code_regex.match(lines[i]) if match: # Check if the caption number is 225 or higher caption_number = int(lines[i-1].strip()) if caption_number >= 225: # Parse the start and end times start_time = datetime.strptime(match.group(1), '%H:%M:%S,%f') end_time = datetime.strptime(match.group(2), '%H:%M:%S,%f') # Subtract the time delta start_time -= time_delta end_time -= time_delta # Format the new time code new_time_code = f'{start_time.strftime("%H:%M:%S,%f")[:-3]} --> {end_time.strftime("%H:%M:%S,%f")[:-3]}\n' # Replace the line with the new time code lines[i] = new_time_code # Write the adjusted lines back to the file with open('Three-Body.S01E13.CHINESE.WEBRip.x264-ION10[eztv.re]_edited.srt', 'w') as file: file.writelines(lines)I saved that as

fix_3body.pyin the same directory as the srt file, and ran it from a terminal (also in that directory) withpython3 fix_3body.py. And that did work—my spouse and I got to finish watching the episode. Hooray! I’m not going to share the edited srt file, but if you’re stuck in the same situation with episode 13, this should get you most of the way to your own copy of a correct-ish subtitle file (I don’t think the offset is exactly 18 seconds, but close enough).I’ll close with a few scattered thoughts:

- I wonder what caused the discrepency? My best guess is that the show was edited, the subtitles were created, and then approximately 18 seconds of dialog-free footage was removed from the shots of Ye Wenjie being moved from her cell and the establishing shot of the helicopter flying over the snowy forest.

- Overall this felt like a success. As I said, I was not really geared up for programming at the time, and while I could have written my own script to fix this subtitle file, it would have taken a while to get started: what language should I use? How exactly does the SRT format work? How can I subtract 18 seconds from a timecode with fewer than “18” in the seconds position (like

00:16:07,020)? Should I have it accept the file as an input parameter? Maybe have it accept which caption to start with as an input parameter? Should that use the ordinal caption number or a timestamp as the position to start from? Even if I wouldn’t have made the same choices as Copilot for those questions, it got me to something nearly functional without my having to fully wake up my brain. - Of course, I did have to make at least two changes to make this script functional. Python is very widely used, especially in ML/NLP/AI (lots of text-mangling!) circles, and GitHub Copilot seems to be considered the “smartest” generally-available LLM fine-tuned for a specific purpose like this. Savita Subramanian, Bank of America’s head of US equity strategy, recently asserted on Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast (yt) that, “we’ve seen … the need for Python Programming completely evaporate because you can get … AI to write your code for you”. And not to pick on her in particular, but in my experience with AI thus far that’s false, especially the “completely evaporate” part. I’m a computer programmer, so you can discount that conclusion as me understanding in my own interest if you’d like.

- I’m not sure there’s a broader lesson to be taken from this, but it struck me that a broken subtitle file feels like the kind of thing that one should expect when sailing the high seas for content. I was surprised when I saw that even Amazon’s copy of the episode had broken subtitles. In the end, controlling a local copy of the episode and its subtitles allowed me to fix the problem for myself. And in fact this kind of strange problem has been surprisingly common on streaming services. My family ran into missing songs on the We Bare Bears cartoon, and Disney Plus launched with “joke-destroying” aspect ratio changes to The Simpsons, just off the top of my head. I don’t believe I can submit my repaired subtitle file to Amazon, but it seems like there’s some kind of process in place to submit corrections to a resource like OpenSubtitles.org.

-

One of the Most University of Chicago Things I Have Ever Read

Well, most humanities at The University of Chicago. This New Yorker profile of Agnes Callard from 2023 is really about one person and her family, but also has so much of what I remember:

- People determined to be honest, deliberate, and thoughtful about their lives.

- Children of faculty who are in a very unusual situation, but seem happy.

- “Night Owls” didn’t exist during my time there, but a late-night conversation series hosted by a philosophy professor sounds like something that I, and many others, would have loved.

- Minimal acknowledgement that one’s intense self-examination and experience may not be generalizable.

- Or maybe I mean something that feels like a strange combination of curiosity and insularity?

- Mental health diagnosis.

- The strong and often-indulged impulse to philosophical discussion.

- Horny professors.

- The kind of restless, striving determination that creates CEOs and political leaders, but applied to something conceptual and niche.

- An figure who is both a dedicated and recognized theoretician in their academic field, as well as the subject of (what sounds like) a kind of gossipy celebrity culture on campus.

It was not a surprise to learn that Dr Callard was also an undergraduate in Hyde Park (before my time). She sounds like the kind of frustrating and exhausting person to be around that I’ll admit I sometimes miss having in my life.

-

When do we teach kids to edit?

My 10 year-old recently had to write an essay for an application for a national scholarship program. He did great, writing 450ish words that were readable, thoughtful, and fun, with pleasantly varying sentences. And then we started editing.

I remember feeling like giving up in my early editing experiences, out of sorrow for the perfect first-draft gems being cut and out of bitterness at (generally) my Mom for having the temerity to suggest changes; if my essay wasn’t good enough then she was welcome to write a different one. My kiddo handled it better than I remember dealing with early editing experiences, by thinking through changes with my spouse without losing confidence in his work. But seeing his reactions and remembering my own made me think about how hard it is to get used to editing your writing.

For a kid, and especially one who tends to have an easy time with homework, it’s annoying to have an assignment that feels complete magically turn back into an interminable work in progress as the editing drags on. But that’s the least of editing’s problems! If the first draft was good, then why edit it all—isn’t the fact of the edits an indication that the original was poor work? How can a piece of writing still be mine if I’m incorporating suggestions from other people? Editing for structure and meaning is especially awful, like slowly waking up and realizing that the clarity you were so certain you’d found was just a dream after all.

I’ve seen my kids edit their work in other contexts: reworking lego creations, touching up drawings, or collaboratively improving Minecraft worlds. So maybe there’s something specific to editing writing that’s more challenging—communication is very personal after all. Or perhaps the homework context is the problem—it is a low-intrinsic-motivation setting. Maybe I just think editing is hard because my kid and I were both pretty good at writing, and some combination of genetics and parenting led to us both having a hard time with even the most gently constructive of criticism. There’s certainly some perfectionism being passed down through the generations in one way or another.

My other child is five years old and is, if anything, even more fiercely protective of her creative work. I want to make this better for her, to get her used to working with other people to evaluate and improve something she has made. But how do you do that as a parent? Should I just start pointing out flaws in my kindergartener’s craft projects? (No, I obviously should not.)

Maybe what’s really changing as kids hit their pre teen years is that creative work must increasingly achieve goals that can be evaluated but not measured. Editing starts out as fixing spelling or targeting a word count, but those are comparatively simple tasks. Does your essay convey what you wanted it to? Is it enjoyable to read? Does your drawing represent your subject or a given style as you intended? I would guess that such aims of editing tend to be implicit for highly-educated parents with strong written communication skills, and not at all obvious to an elementary school student. I’m not sure how much groundwork can be laid for these questions in kindergarten, but the next time I’m editing something with one of my kids, I think I’ll try explicitly introducing those goals before getting out the red pen.

-

Was the Cambrian JavaScript Explosion a Zero Interest Rate Phenomenon?

A kind of cliché-but-true complaint common among programmers in the late 2010’s was that there were too many new JavaScript things every week. Frameworks, libraries, and bits and pieces of tooling relentlessly arrived, exploded in popularity, and then receded like waves on a beach. My sense is that this pace has slowed over the last few years, so I wonder: was this, too, a ZIRP phonemon, and thus a victim of rising interest rates along with other bubbly curiosities like NFTs, direct-to-consumer startups, food delivery discounts, and SPACs?

I’ll admit: I can’t say I’m basing this on anything but anecdotes and vibes. But the vibes were strong, and they were bubbly. People complained about the proliferation of JS widgets not because of the raw number of projects, but because there was a sense that you had to learn and adopt the new hotness (all of which still seem to be going concerns!) in order to be a productive, modern, hirable developer. I think such FOMO is a good indicator of a bubble.

And I think other ZIRP-y factors helped sustain that sense that everyone else was participating in the permanent JavaScript revolution. What could interest rates possibly have to do with JavaScript? Let’s say you have $100 to invest in either a startup that will return a modest 2x your investment in 10 years, or a bank account. If interest rates are 7%, your bank account will also have (very nearly) doubled, and of course it’s much less risky than a startup! If interest rates are 2%, your $100 bank account will only end up about $22 richer after a decade, so you might as well take a chance on Magic Leap. It also means that a big company sitting on piles of cash might as well borrow more, even if they don’t particularly know what to do with it. So all of that is to say: low interest rates meant there was cheap money for startups and tech giants alike.

Startups, for their part, are exactly the kind of fresh start where it really does make sense to try something new and exciting for your

interactive demoMVP. If you’re a technical founder with enough of a not-invented-here bias—a bias I’ll admit to being guilty of—then you might well survey the JavaScript landscape and decide that what it lacks is your particular take on solving some problem or other. Here’s that XKCD link you knew was coming.As for the acronymous tech giants, there’s been recent public accusations that larger firms spent much of the 2010s over-hiring to keep talent both stockpiled for future needs and also safely away from competitors (searches aren’t finding me much beyond VC crank complaints, but I’d also gotten this sense pre-pandemic). Everyone loves a good “paid to do nothing” story, but I think most programmers do want to actually contribute at work. A well-intentioned, ambitious, and opinionated programmer might well pick up some slack by refactoring or reimplementing some existing code into a brand new library to share with world. If nothing else, a popular library is a great artifact to present at your performance review.

I started thinking about this in part because it frustrates me how much programming “content” (for lack of a better word) seems to be geared towards either soldiers in corporate programmer armies or individuals who are only just starting their company or their career: processes so hundreds can collaborate, how-to’s fit only for a blank page, or advice for your biannual job change. There’s probably good demographic reasons for this; large firms with many programmers have many programmers reading Hacker News. But something still feels off about this balance of perspectives, and you know what? Maybe it’s all been a bubble, my opinions are correct, and it’s the children who are wrong.

As interest rates proved to be less transient and some software-adjacent trends were thus shown to have been bubbles, a popular complaint was to compare something like crypto currency to the US railroad boom (and bust) of the 19th century—the punchline being that at least the defunct railroads left behind a quarter-million miles of perfectly usable tracks.

So what did we get for the 2010’s JavaScript bubble? Hardware (especially phones), browsers, ECMAScript, HTML, and CSS all gained a tremendous amount of performance, functionality, and complexity over the decade, and for the most part a programmer can now take advantage of all that comparatively easily. The Hobbesian competition of libraries left us with the strongest, and it’s now presumably less complicated trying to decide what to use to format dates.

Then again, abandonware is now blindly pulled into critical software via onion-layered dependency chains, and big companies have taken frontend development from being something approachable by an eager hobbyist armed with a text editor, and remade it in their own image as something to be practiced by continuously-churning replaceable-parts engineers aided by a rigid exoskeleton of frameworks and compilers and processes.

So yes, “in conclusion, web development is a land of contrasts“. To end on a more interesting note, there are two projects that I think could hint at what the next decade will bring. Microsoft’s Blazor is directly marketed as a way to avoid JavaScript altogether by writing frontend code in C# and just compiling it to WebAssembly (yes, that’s not always true because as usual Microsoft gave the same name to four different things). Meanwhile htmx tries to avoid this whole JavaScript mess by adding some special attributes to HTML to enable just enough app-ness on web pages. I would never bet against JavaScript, but it’s noteworthy that both are clearly geared towards people frustrated with contemporary JS development, and it’ll be interesting to see how much of a following they or similar attempts find over the next few years.

-

Prevent Unoconv From Exporting Hidden Sheets From Excel Documents

At work we use unoconv—a python script that serves as a nice frontend to the UNO document APIs in LibreOffice/OpenOffice—as part of our pipeline for creating preview PDFs and rasterized thumbnail images for a variety of document formats. Recently we had an issue where our thumbnail for a Excel spreadsheet document inexplicably didn’t match the original document. It turned out that the thumbnail was being created for the first sheet, which didn’t display in Excel because it was marked hidden. I couldn’t find any toggle or filter to prevent unoconv from “printing” hidden sheets to PDF, and ended up having to just add a few lines to unconv itself:

# Remove hidden sheets from spreadsheets: phase = "remove hidden sheets" try: for sheet in document.Sheets: if sheet.IsVisible==False: document.Sheets.removeByName(sheet.Name) except AttributeError: passI added that just before the “# Export phase” comment, around line 1110 of the current version of unoconv (0.8.2) as I write this.

I don’t know why this wasn’t the default behavior in LibreOffice, since non-printing export targets like HTML correctly skip the hidden sheet—shouldn’t your printout match what you see on screen?

I’m sharing this as a blog post (rather than submitting a pull request) because unoconv is now “deprecated” according to its GitHub page, which recommends using a rewrite called unoserver in its place. That sounds nice, but for now our unoconv setup is working nicely, especially now that we aren’t creating thumbnails of hidden sheets!

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.